A new study led by researchers of The Cyprus Institute, has produced the first global dataset of ultrafine particle (UFP) concentrations.

As noted in a relevant press release, these tiny particles are invisible to the human eye but can penetrate the lungs and enter the bloodstream, posing a significant threat to human health. The study’s findings reveal major differences in UFP concentrations between clean natural environments and urban areas, offering an important new tool for understanding how ultrafine pollution affects public health worldwide.

It has long been established that air pollution has significant long-term health impacts, linked to millions of excess deaths globally. Air pollutants with diameters less than 10 μm (PM10) and 2.5 μm (PM2.5) have long been linked to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. While growing evidence suggests that ultrafine particles (UFPs), which are significantly smaller with a diameter of less than 0.01 μm, are also a major health risk due to their ability to reach critical organs such as the lungs and the bloodstream. Despite this, global data on UFP levels has been extremely limited.

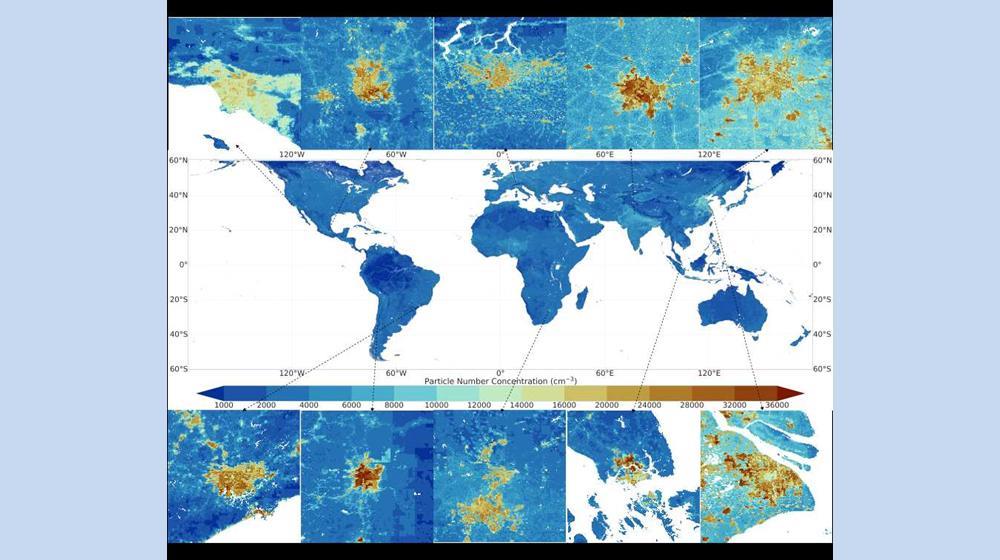

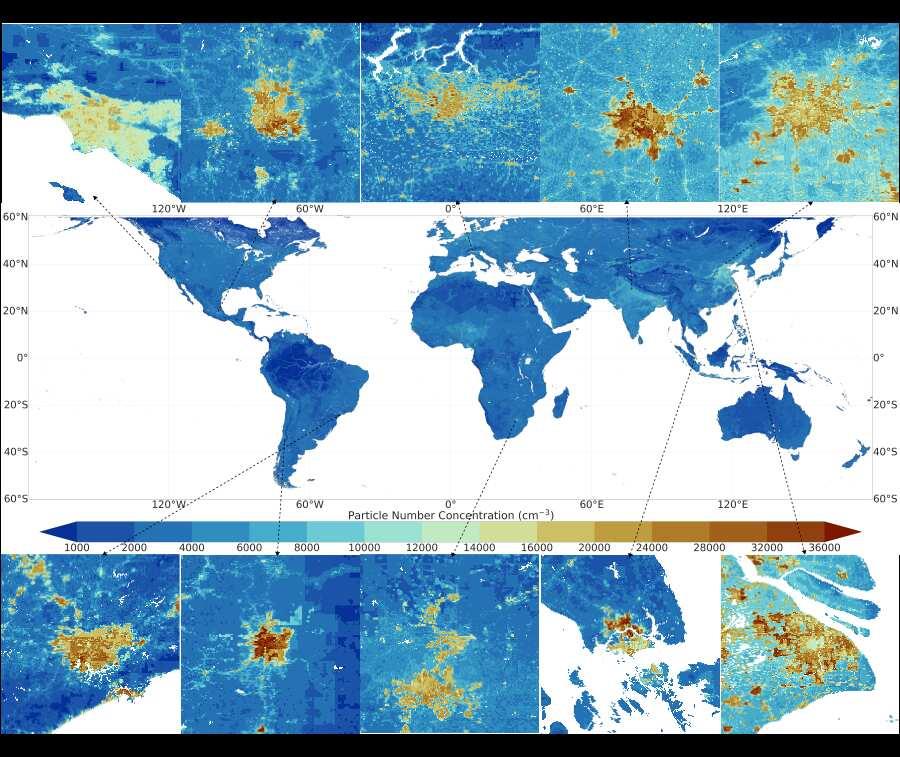

To address this gap, researchers of the Climate and Atmosphere Research Center (CARE-C) and the Computation-based Science and Technology Research Centre (CaSToRC) of The Cyprus Institute, have developed a machine learning model using real, ground-station measurements. The model generates high-resolution global UFP maps at high spatial resolution (1 km) spanning the 2010-2019 decade, accurately reflecting large-scale spatial patterns of ultrafine pollution.

The results published in Nature’s Scientific Data journal, show that pristine environments, such as forested and unpopulated regions, often contain only a few thousand particles per cubic centimetre, whereas major cities routinely exceed 40,000, with ultrafine particles accounting for roughly 91% of all airborne particles by number. There is currently no specific concentration limits set for UFPs. Though notably, the new EU Air Quality Directive (EU2024/2881), expected to be implemented starting 2026, requires member states to monitor UFP in ambient air, with results to inform decisions regarding the introduction of future limits in line with World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines.

As Dr Pantelis Georgiades, lead author of the study, stated, “This new global dataset enables scientists, governments, and public-health organisations to identify pollution hotspots, assess health impacts, and design targeted interventions. By revealing the worldwide distribution of ultrafine particles in such detail, The Cyprus Institute’s research provides a crucial foundation for addressing one of the most overlooked threats to human health.”