When he was a little boy, Symeon Kassianides would follow his mother, a prominent figure in the art world, as she coordinated and installed exhibitions.

By the time Gloria Kassianidou launched the now-iconic Gloria Gallery in Nicosia in 1977, her son had already been steeped in the rhythms of the art scene. As the first gallery for modern art to open in Cyprus after the Turkish invasion, it quickly became a hub of cultural life and a defining anchor for artists on the island.

“Growing up in that environment affected me greatly in many ways,” he says. When Kassianides was 16, he returned home from school one day to find his bedroom redecorated – his Led Zeppelin and Farrah Fawcett posters had been replaced by framed paintings. “The message was clear: it was time for me to grow up,” he says, laughing.

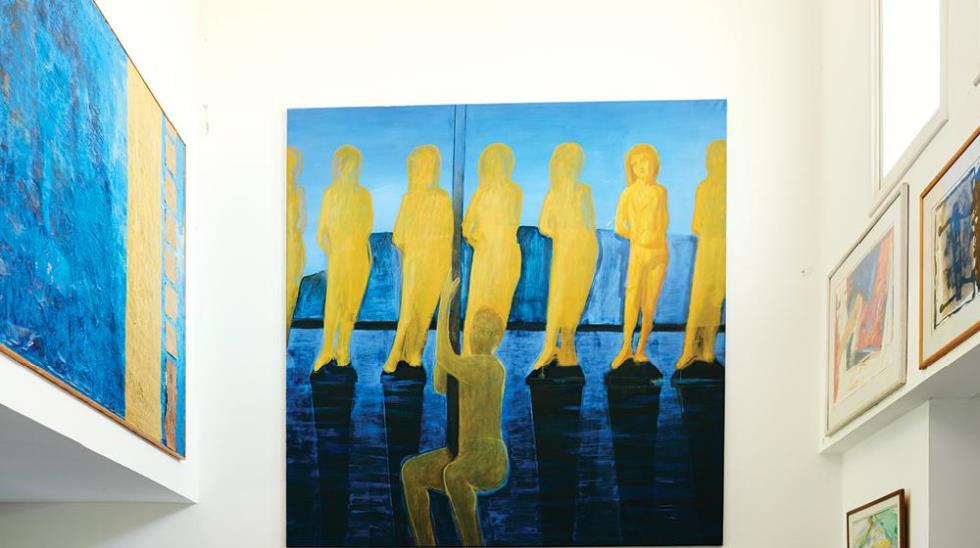

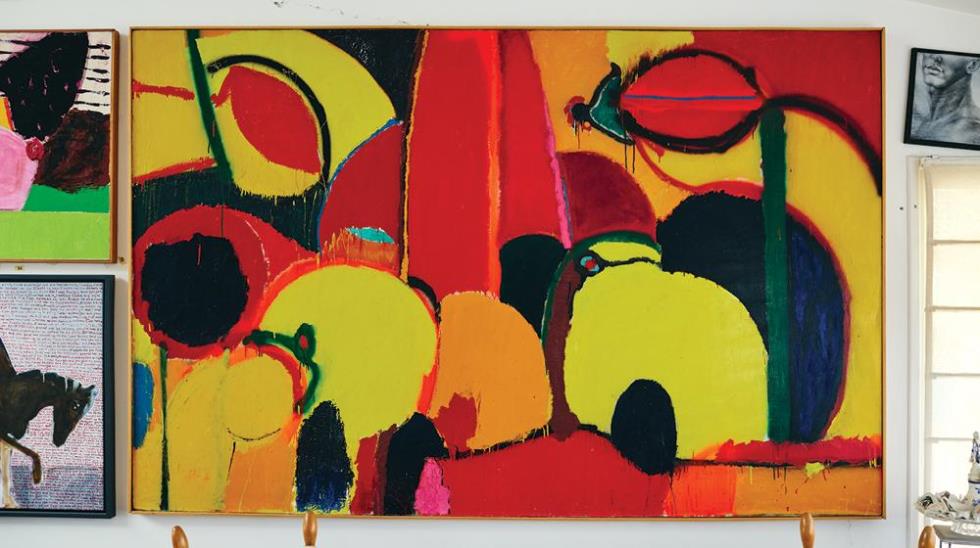

When entering his home in the Geri area of Nicosia, one is struck by the sheer number of paintings covering the walls – there’s barely any space left. Indeed, some works don’t even have a place to go and remain wrapped in canvas or propped up gently against furniture. “I wish I followed a specific process for where to hang each painting,” Kassianides says with a smile, “but, as you can see, they’re everywhere. We said that this weekend we’ll start putting some of them up.”

Several of the homeless pieces are from his company’s previous offices, where they once adorned the walls but didn’t make the move when the company relocated. Kassianides founded Hyperion Systems Engineering back in 1993. Today, he serves both as Chairman and CEO. He grew the software company into a global player, with three companies under one roof offering consulting, advisory and software engineering solutions to the oil and hydrocarbons industry. It serviced some of the sector’s major players: Saudi Aramco, Shell, ExxonMobil, and so on. And even though the pandemic forced some hard choices, from layoffs to shutting down offices globally and selling parts of the business, Kassianides managed to steer the company back into profitability.

“So,” he adds, “what was done to me I’ll now do for my three boys, who are all away. We’ll put the paintings in their rooms,” he says, amused.

One of his favourite paintings is by Cypriot artist Nikos Kouroussis, an abstract work that was among the pieces that he found hanging on his bedroom wall at 16. It is now in the living room, surrounded by the abstract expressionism of Welsh artist Glyn Hughes, the confident brushwork of Famagusta-born Dimitris Michlis, and the masterful colour work of Kikos Lanitis. Still, if pressed, Kassianides struggles to pick a favourite style. “I’m fascinated by everything, from naïve art to the old masters, from abstract to contemporary,” he says. “I mean, look over there.” He points above the doorframe in his home office, where we’ve retreated for some cool air conditioning as the summer sun burns hot. “That’s a Venezuelan tribal mask used in traditional ceremonies,” he explains. For Kassianides, every form and style has something to say. With figurative art, the meaning is often right there. But the more abstract you go, the more it’s up to the observer to create their own story. “It’s not so much about what the artist wants to portray – it’s about what you make of it. It becomes a kind of philosophical journey,” he adds.

When it comes to acquiring new art, Kassianides follows the same instinctive drive, buying what moves him. “You see something and you know it’s a little bit different; it speaks to you,” he says. With the Gloria Gallery still going strong, holding at least two exhibitions a month for nearly 50 years, there are no real obstacles to discovering new work. “I was in Madrid last week. We visited the Prado, the Reina Sofia and saw some major collections. Then we went to a bar where they had a Matisse, a Picasso. You like all that stuff, right? It gives you a certain satisfaction. But what thrills me most is discovering young artists who have something new to say. I get more excited by the new.”

So, is there an overlap between art and business?

Kassianides pauses to contemplate. “I think,” he finally says, “I have lived a parallel existence. Art is defined by creativity and the need to express something new, something different. I think that carried through into business, by trying different products, expanding to different countries and being open to different things. To break new ground, you need to be willing to see things differently, something which, I believe, comes from the influence of art.”

But, there’s one key difference: in business, knowing when to say no or stop is a matter of survival. For Kassianides, art can afford to stay with the message because it follows a belief whereas in business, adaptability and evolution are expressed in much harsher ways. Why is that?

“Because business is survival; art is expression,” he replies, without missing a beat.

If he had the chance, Kassianides says he’d be curious – and it is curiosity, nothing more – to have lunch with American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, best known for his comic book-inspired scenes, such as two aircraft shooting at each other with the word Whaam! exploding across the canvas in bold letters. “I’m intrigued by what he paints,” he says. “He always has a theme but it’s always a different one. It’s kind of like Banksy, or maybe Banksy is an evolution of that. There’s not necessarily a relationship between the themes but he probably captures the moment.”

These days, Kassianides will forgo a piece if someone else expresses interest. “It’s a good way to get someone interested in art. And I stopped being possessive many years ago,” he jokes. He wants more people to embrace the arts, convinced that they’ll find the same fulfilment he has. “In Cyprus,” he notes, “we sometimes think you have to buy something to engage with art. But the real benefit is in the experience – whether you buy or not is totally unrelated to the sense of fulfilment.”

(Photos by TASPHO)