Harry Mavromichalis on why figuring out its voice can be a challenge for the Cyprus film industry

Marianna Nicolaou 07:05 - 30 December 2023

New York-based Harry Mavromichalis, director of Olympia, the acclaimed 2018 documentary on Award winning actress Olympia Dukakis, talks about the directing and editing process, his view of film critics and the state of the Cyprus film industry.

“Since I was a kid, I wanted to be an actor, but then I did some plays at school, and I realised that I was really bad!” says Harry Mavromichalis, laughing. “While I was finishing the army, my cousin asked me if I could go and see her at her dance school. So I went, and I was blown away by what was happening.”

Mavromichalis was enraptured by the ability to express emotions and tell stories through bodily movement but, as happens in many love stories, at that moment he was influenced by his parents’ wishes and, instead of becoming a dancer, ended up studying Spanish Literature and Communications. However, in what sounds like a scene from a movie in which the hero experiences an epiphany, just before he was due to graduate, he received a letter that was to change his life forever. It was from a close friend who was having a very hard time and so he rushed to her side. By the time she was out of the woods, Mavromichalis was a changed man; one who had decided to chase his dreams.

“That experience made me realise that I had to live my life fully, I couldn’t live my life based on other people’s ideas and beliefs! And I thank her for that, because how many people live their lives based on other people’s wishes, rather than what they themselves want to do?”

After studying and then working professionally as a modern dancer and choreographer, he went back to school and received his MFA in Film Directing from New York University. Today he is known as a writer, director, producer and production designer of multiple short films, music videos and commercials.

“I love magical realism” he tells me. “Even when I was a choreographer, a lot of my work revolved around magical realism. Gabrielle Garcia Marquez has been a big influence and Guillermo del Toro another.” After this revelation, I am not surprised to hear that Mavromichalis was for some time adamant about not working on documentaries. After obtaining his MFA in Film Directing, he wanted to do what he then described as “real films” he tells me, in a mocking voice, unabashedly acknowledging his mistaken thinking.

But it was not until a film he had meticulously worked on to shoot in Cyprus was put on hold due to the 2011 financial crisis and the subsequent haircut that left him in an artistic limbo, in combination with a documentary on Carol Channing he watched at the 2011 Tribeca Film Festival, that his eyes were opened to the vast genre and film style that existed under the documentary umbrella. “‘Oh my God, someone should make a documentary on Olympia Dukakis!’, I exclaimed! And my husband said, ‘Well, why don’t you do it? You are a filmmaker!’”

Olympia Dukakis was a fascinating woman, he tells me, and just being in her commanding presence was a gift for him. He was utterly and overwhelmingly enchanted by her. As a woman who did not care about decorum, she laughed loudly and worked intensely, asking from people what they could give, rather than demanding everything. This, he says, shifted his outlook on human relationships, wiping away any feelings of guilt and replacing them with a deeper and more substantial comprehension of human nature, for which he will eternally be grateful.

“She was one of the smartest people I’ve ever met,” he says. “She read a lot, she knew about everything, she could talk about anything. But also, when it came to the things that she was really interested in, she dove really deep; there was nothing fluffy about Olympia. She changed who I am; at that specific time, she definitely turned me into a better person.”

Mavromichalis tells me that he is working on more documentaries right now, and his greatest inspiration has been none other than human nature. “I just meet interesting, fascinating people and a voice says, ‘You’ve got to do this. Their stories need to be told.’ And then I just dive in. I don’t have a script! You know, history or bio documentaries often have a script with narration and then they bring in the footage and form a timeline. I can’t do that!” he tells me, with a sharp movement of his hand. “Because I feel that it loses its spontaneity and misses the dynamism of the person in question. So, I dive in, I get a lot of footage, and then I go into the studio with my editor and we start editing.”

Bringing your vision to life and connecting with audiences is no easy task. Indeed, Mavromichalis went on his own odyssey to find an editor who could match his style. “Good editors are expensive,” he tells me. “We’re talking about anywhere between $1,500 to $10,000 a week, and it takes a specific kind of person to be OK, being alone in a room, handling material. That’s when I realised that the tricky part in a documentary is the editing, not the shooting. It took me three years to shoot and four years to edit. But it was worth it, I look at my film, and I wouldn’t do anything different.”

Right now, he is focusing on Glorious Broads and will soon start work on finishing the pitch trailer of the project. “Along with my partner, Maryjane Fahey, we decided to do a show about women over 50 talking about sex, because there’s nothing out there. It’s what you might call the female version of ‘locker talk’. We decided to create a social media presence before pitching it to Netflix, Hulu and HBO. I love this project, because we’re building a community. We started with TikTok, we stopped women over 50 in the street, and asked them different questions about life regrets and advice. Then we delved into Instagram and now we have around 162,000 followers.”

“What does success and failure mean to you? Are these concepts connected to awards or critics?” I ask. “To neither!” he exclaims. “I want people to see my film; that’s the most important thing. If it brings more money or critical acclaim, that’s great too. We’ve had many reviews, and all of them were amazing, except one, from the New York Times, which was like a big slap in the face. A friend of mine asked me, ‘After reading that review, would you change anything?’ and my answer was ‘no’,” he says in a light tone. “I realised then that you either have a brain that’s poetic, that can understand depth and different things that are given to you, or you have a ‘square’ brain. One is not better than the other; it just means that not everybody will understand your work. What’s important to me is to be able to do things that fulfil me, allow me to meet interesting people and collaborate with them – it just feeds me.” As he explains, viewership is a reflection that his work is appreciated, “so of course, people’s reception is way more important than the critics’ view.”

In true Alfred Hitchcock fashion, Mavromichalis loves attending the screenings of his work incognito, sitting in the back and observing the audience’s reaction. “There is nothing better, nothing better!” he says passionately. “The laughing, the crying, it’s a different experience seeing it live, rather than people telling you they watched it on television or computer.”

It is obvious by now that Mavromichalis is an intellectually playful man, one who enjoys questioning certainties and extremely comfortable in his own skin. When I ask him to assess the Cyprus film industry, he doesn’t hold back: “I think the island’s film industry has grown immensely in the last 20 years. There used to be one person who made one good film and maybe another one five years later but now you see people doing really amazing stuff so often. I have many good friends whose films are going out to all these different countries and they’re doing so well. I think the challenge for Cyprus is figuring out our voice. Because, as a nation, we have an identity crisis; we don’t know who we are. Maybe we did 200 years ago, but definitely since I was born, we have not had a clear identity of who we are,” he says shaking his head.

After we finish talking, one particular part of our interview keeps replaying in my head: “How many people live their lives based on other people’s wishes, rather than what they themselves want to do?”

Harry Mavromichalis may have taken some time to understand what he needed to do with his life but he has clearly lived it to the full ever since.

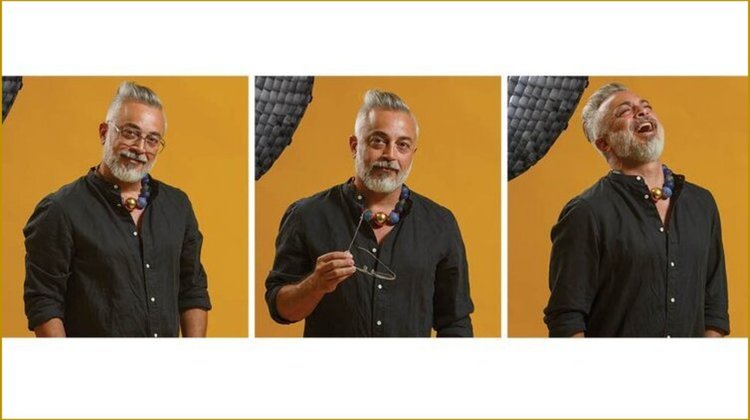

HARRY MAVROMICHALIS

Harry Mavromichalis has dual US and Cypriot citizenship. He moved to the US for college after completing his military service in Cyprus. He has a BA in Spanish Literature and Communications from Rutgers University and a dance diploma from the Alvin Ailey American Dance Center. He worked as a professional dancer and choreographer for many years with his company “Dance Anonymous”. He received his MFA in Film Directing from New York University. He is a huge supporter of LGBTQ rights and was directly involved in the first ever Gay Pride Parade in Cyprus while curating the first ever LGBTQ film festival of the island.

(Photos by: Michael Kyprianou)

This interview first appeared in the December 2023 edition of GOLD magazine. Click here to view it.